Why “partner or die” defines innovation in 2026

In 2026, ambitious products no longer fail because the idea is weak; they fail because the partnerships needed to scale them break down. As AI, robotics, and connected systems reshape how we design and manufacture, no single team has all the capabilities to take an idea from sketch to market. That is why “partner or die innovation” has become the quiet operating rule behind the most successful launches.

For designers, makers, and product leaders, this shift is both a threat and an opportunity. On one hand, it means you must share control with external partners. On the other, it lets you build products that would have been impossible inside one studio or factory.

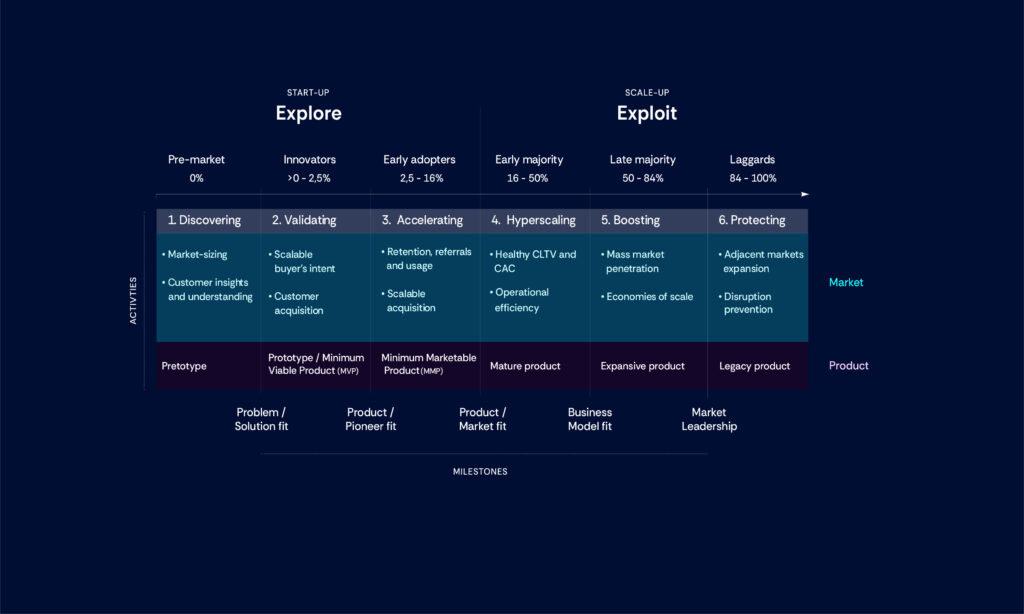

Partner or die innovation starts where prototypes stall

Many teams are still organized as if a brilliant prototype automatically leads to a successful product. In reality, most promising concepts stall at the point where they need contributions from manufacturers, software partners, logistics providers, or digital platforms. At that moment, innovation becomes less a design problem and more an operating‑model problem.

Instead of asking “Is the concept good enough?”, leaders now have to ask “Who owns the cross‑boundary decisions, shared roadmaps, and joint resources that will make this work at scale?”. When no one owns these connective pieces, partnerships drift, deadlines slip, and politically safe compromises water down even the strongest ideas.

Designing partnerships like you design products

To make partner or die innovation work, you need to treat your collaboration model as deliberately as you treat form, ergonomics, and user experience. Before you cut the first piece of wood or brief the first robotics integrator, you should map four elements:

- Who must co‑create: manufacturers, engineers, UX teams, marketers, digital channels, and after‑sales partners.

- What decisions they own: specifications, timelines, quality thresholds, brand and IP boundaries.

- How information flows: shared roadmaps, design systems, and data interfaces instead of ad‑hoc emails.

- Which incentives align them: revenue sharing, joint KPIs, or equity and technology integration that reward shared success.

Crucially, you also need explicit “bridgers”. People accountable for translating across disciplines and organizations, rather than relying on informal heroes who fix problems in the background. These bridgers curate the right partners, interpret different working styles, and keep the combined effort moving when complexity spikes.

For a deeper exploration of how technology is reshaping design roles, you can read my article “Arm Revolution: What designers must know in 2026,” which shows how new chip architectures force designers to coordinate closely with silicon and AI experts. This kind of cross‑boundary mindset is exactly what turns fragile prototypes into robust, scalable products.

Partner or die innovation in furniture and tech products

Furniture and tech products sit at a particularly interesting intersection of materials, digital layers, and manufacturing constraints. A table that integrates sensors, lighting, or charging surfaces is no longer just a piece of furniture. It is a small system that depends on electronics partners, firmware developers, and often cloud or app ecosystems.

In this context, partner or die innovation means:

- Working with manufacturers early to validate whether your joinery, tolerances, and finishes remain feasible once electronics and robotics enter the production line.

- Involving hardware and AI partners at concept stage, not after the form is “locked,” so that power, thermal, and update constraints are built into the design language.

- Defining shared ownership over failure modes: who responds if a sensor fails, a firmware update breaks functions, or a batch of materials behaves differently under robotic assembly.

Because the intelligence in these products increasingly lives in silicon and software, Arm’s ecosystem provides a useful example: its licensing model lets partners customize AI‑optimized chips for mobile and edge devices while Arm remains a foundational layer. Similarly, your furniture and tech projects can use modular architectures that allow different partners to innovate on distinct layers without destabilizing the whole system.

From persona to prototype: designing people into the process

Partner or die innovation is not only about contracts and roadmaps; it is also about how you represent the humans who will use and sell your product. UX personas, when grounded in real research, help keep user needs visible across dispersed teams that might otherwise optimize for their own silos.

If your manufacturers push for cheaper materials, your developers argue for feature creep, and your marketing team wants spectacle, personas act like a shared compass that keeps everyone anchored to the same user story. Used well, they reduce bias, prevent costly misaligned features, and provide a common language between designers, engineers, and business leads.

For a more narrative take on how personas shape design empathy, you might explore my article “Persona studies provide a better design effortless,” which connects user research with more effortless decision‑making for creative teams. When personas are integrated into your partnership model, they become another bridge across organizational boundaries rather than a static research artifact.

Scaling craft: from atelier to ecosystem

Behind all of this sits a bigger mindset shift: scaling is itself a design problem. The craft is no longer only in the physical prototype or the digital mock‑up; it is in orchestrating the ecosystem that can deliver the same level of quality at 10x or 100x volume.

You can treat this as a story: the artisan prototype is the protagonist, and every partner (manufacturer, coder, logistics provider, retailer), is part of the supporting cast that either preserves or distorts the original intent. By deliberately designing roles, handoffs, and feedback loops, you give your product a much better chance of surviving this journey without losing its soul.

If you want to see how this narrative has played out over decades of design history, the tribute to Peter Schmidt highlights how consistent collaboration across brands, manufacturers, and disciplines built a lasting body of work. His example quietly underlines today’s reality: the designers who thrive in a partner or die innovation landscape are those who design relationships as carefully as they design objects.

“If you want a concrete roadmap for how designers should respond to these shifts in silicon and AI, you must read ‘Arm Revolution: What designers must know in 2026’ before your next product decision.”

Suggested external links

HBR – “Why Great Innovations Fail to Scale” (deep dive into partnership‑driven innovation).

Interaction Design Foundation – personas in UX design (practical persona guidance).